Photo by Park Troopers on Unsplash

We’ve all probably heard a coach, mentor, or teacher say “it’s not only what we know, it’s who we know” at some point in our lives. Some of us already believe it, though few of us really understand what it actually means. Many of us limit this way of thinking to our careers or a narrowly-defined version of success. We don’t appreciate how influential who we know is to all aspects of our lives. Nor do we appreciate that who they know can be just as influential. Who we know and who they know together influence what we know, what we do, and our success.

Who we are influences who we know

The first sentence of the often-cited paper “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks” reads “similarity breeds connection.” Homophily is defined as “the tendency for people to seek out or be attracted to those who are similar to themselves”. They go on to say,

“Homophily limits people’s social worlds in a way that has powerful implications for the information they receive, the attitudes they form, and the interactions they experience. Homophily in race and ethnicity creates the strongest divides in our personal environments, with age, religion, education, occupation, and gender following in roughly that order.”

After a few years in London, I proudly announced that I wanted to make more “old” friends. I didn’t mean friends that I’d know for a long time, I meant friends that were at least 20 years older than me. Between my industry, living environment, and hobbies, I just wasn’t meeting enough people in that life stage. As a result, the diversity of perspectives I had to draw from was limited.

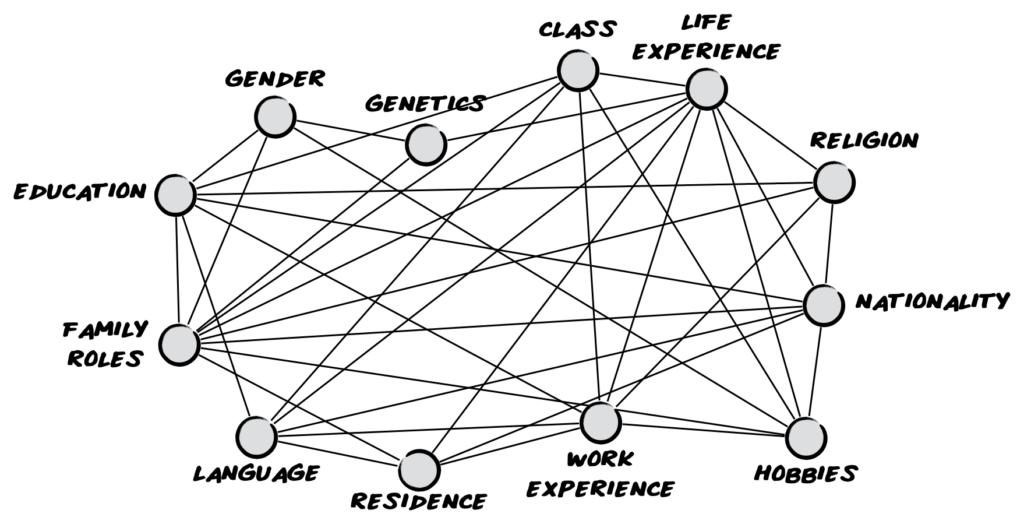

You are a network explores the idea that we have many attributes that we identify with above and beyond typical demographics. All of those attributes have relationships to each other (e.g. our family role is related to our gender). This can insulate us within a community high in homophily, but it can also create bridges to people that share identities that transcend typical boundaries (e.g. mothers and fathers).

“Seeing ourselves as a network is a fertile way to understand our complexity. Perhaps it could even help break the rigid and reductive stereotyping that dominates current cultural and political discourse, and cultivate more productive communication. We might not understand ourselves or others perfectly, but we often have overlapping identities and perspectives. Rather than seeing our multiple identities as separating us from one another, we should see them as bases for communication and understanding, even if partial.”

I remember the very first night I was in Hong Kong on business. My host took me to a cramped cafe just off Temple Street Night Market and ordered two bowls of sweet red bean soup. Never in my life had I seen beans sweetened with sugar and served as a dessert. It absolutely blew my mind and quickly became a favourite. Growing up in New York, I could have easily come across it given the large Cantonese population, let alone the countless other Asian cuisines where this is common. Whether foods are sweetened or not is rarely controversial (marshmallow-topped sweet potato casserole comes to mind), but who we know influences what we think is right or wrong, good or bad, and normal or not normal.

I remember the very first night I was in Hong Kong on business. My host took me to a cramped cafe just off Temple Street Night Market and ordered two bowls of sweet red bean soup. Never in my life had I seen beans sweetened with sugar and served as a dessert. It absolutely blew my mind and quickly became a favourite. Growing up in New York, I could have easily come across it given the large Cantonese population, let alone the countless other Asian cuisines where this is common. Whether foods are sweetened or not is rarely controversial (marshmallow-topped sweet potato casserole comes to mind), but who we know influences what we think is right or wrong, good or bad, and normal or not normal.

Paul Gompers and his colleagues’ study of the venture capital industry surfaces both the widespread homophily and the financial benefit of diversity. They looked at almost 3 decades of investment and performance data and found that if two people had the same ethnic background, it increased their chances of investing together by almost 23%. Similarly, if two people went to the same university, the likelihood of them investing together increased by more than 20%.

Unfortunately, co-investment between people that had these similarities resulted in worse investment outcomes. People with degrees from the same university who invested together had 22% lower chance of investment success. Investing alongside people with the same ethnic background reduced the probability of success by 25%. The researchers believe these results stem from ‘group think’, poor decision making by a group of very similar investors after making the investment.

We rarely reflect on just how impactful this is. We are much more likely to surround ourselves, intentionally or not, with people that are very similar to us. The people we know are likely to do the same. This impacts our beliefs and values, which influence the choices we make throughout life.

Who we know influences what we know

“Chance favors the connected mind” is a popular quote from the author Steven Johnson. In his book, Where Good Ideas Come From, he weaves together several concepts to highlight the role community plays in supporting innovation. He talks about the role of English coffeehouses in bringing the Age of Enlightenment and Parisian salons in the rise of Modernism.

Another famous example is the Solvay Conference for chemistry and physics, which started in 1911 and encourages discussion over presentation. Incredibly, 17 of the 29 attendees from 1927 have won Nobel prizes including Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Werner Heisenberg. Similarly, the Harlem Renaissance is considered a golden age for arts and culture in the US, attracting creators as diverse as Aaron Douglas, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston. A more recent example is the PayPal Mafia, a group of almost 2 dozen people who all worked at PayPal. Since then, they have founded some of the world’s most successful companies such as Affirm, Kiva, LinkedIn, Palantir, SpaceX, Yelp, and YouTube.

One of the key concepts Johnson includes is called the “adjacent possible”, a theory by Stuart Kauffman from the University of Pennsylvania. The theory describes how what’s possible emerges from interactions between what currently exists. Since then, Vittorio Loreto and fellow researchers have created models to explain how this happens, sometimes creating something easy to imagine, other times creating something completely unexpected.

Of course, we and the people we care about are not always worried about coming up with truly new ideas. Interestingly, the adjacent possible also applies to ideas and information that aren’t new to the world, but are new to us individually. After resigning from a C-level role with a startup in 2014, many friends asked me what I wanted to do next. I told them I wanted to be a producer for startups, like producers develop boy bands. After a quick chuckle they’d say, “Well, since that job doesn’t exist, what are you actually going to do?” At that point, the first venture studio idealab was already 16 years old and the first talent investor Entrepreneur First was going on 3 years. These organisations, and many others like them, produce founding teams to start companies. Me and the people I knew just didn’t know about them yet.

Who we are connected to influences every aspect of our lives: what solutions to problems we can find, what career paths we are aware of, and even what treatment options are available to us. Basically, who we know impacts what we know to be possible.

Who we know influences what we do

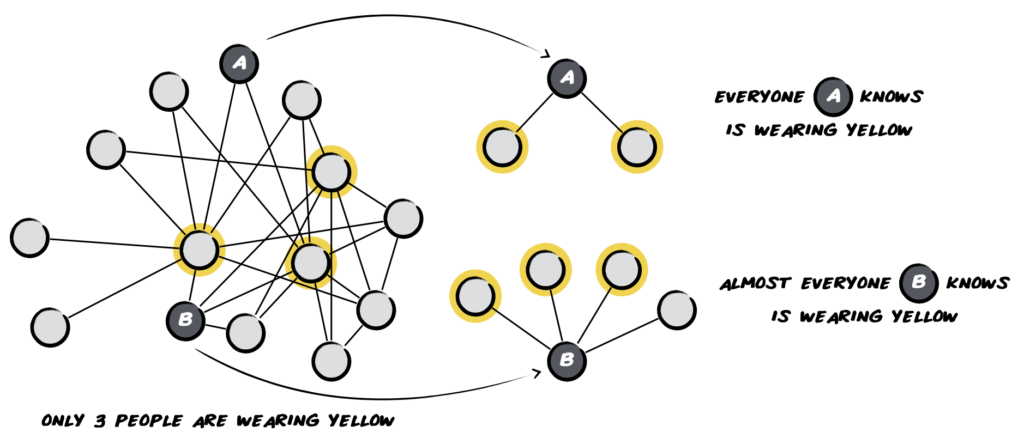

Kristina Lerman and her colleagues studied many real-world communities and identified a phenomenon they describe as the “majority illusion“. Since some people have many more connections than others, they show up more frequently in groups. We might see a habit, opinion or even a product being used by most of our group, even if it is not common overall.

Of course, the subject is not always so benign. Lerman and her collaborators found this illusion in political communities as well as groups of teenagers using drugs and alcohol. Any time we perceive a habit or opinion to be common, keep in mind that our perception might be distorted based on who we know.

Conformity is a popular topic of psychological studies. Some of the most infamous were conducted in the 1950s by Solomon Asch from Swathmore College. In “A Minority of One Against A Unanimous Majority“, he shared the results of a series of studies highlighting the power of these social pressures. He would ask a group of people to answer a question that had an obvious correct answer. He found that almost a third of the time, people would say the wrong answer to the question if 3 or more people publicly and unanimously said the wrong answer before them.

In follow up studies, he found that 2 other people saying the wrong answer out loud first resulted in conformity 13% of the time and that 4 or more people doing the same thing didn’t increase conformity above 32%. Thankfully, having just one ally reduces our chances of conformity in this scenario. Also, being able to share our answer in private reduces our pressure to conform. Regardless, the answer to “if everyone you know jumped off a cliff, would you?” is yes, more often than we might think.

Who we knows influences our success

Mark Granovetter’s paper, “The Strength of Weak Ties”, is the classic example. The prevailing belief then, which still persists today, is that strong connections or ties between people are all that matter. A weak tie is how we might describe a connection between two people who are acquaintances. In his work, Mark used the example of finding a new job to demonstrate that strong ties often had access to basically the same information. As a result, they weren’t able to help each other identify new job opportunities.

In A Thank You Note to My Weak Ties, I mention just a handful of ways that weak ties have had an impact on my life. They have certainly unlocked career opportunities, but they have also exposed me to magical experiences and helped me forge lasting friendships. It’s also interesting to reflect on the chains of introductions (who introduced who). I have one chain that is 8 people long and counting. The number of opportunities that chain has produced alone is staggering.

In The Formula, Albert-Laszlo Barabasi lays out a set of laws about success, backed by work he and a team of researchers completed at the Network Science Institute of Northeastern University. One of the laws states, “Performance drives success, but when performance can’t be measured, networks drive success”. His team demonstrated this law was by studying the success of artists based on prices paid for their work at auction. Since the performance of artists and the quality of their art can’t be measured objectively like an athlete, it’s a fantastic example of where who we know drives outcomes.

First, they made a map of galleries and museums based on whether they ever displayed the same piece of art. Then they mapped where both successful and unsuccessful artists displayed their work over time to understand their career path. They found that artists that displayed their work at well-respected galleries and museums early in their career significantly increased the chances they could continue to do so. They were also more likely to fetch high prices at auction. If the artist started their career displaying art in places that were not as well-respected, they were more likely to drop out and stop making art at all.

For better or worse, it doesn’t end there. Not only does who we know matter, but who those people know influences us as well. In part 2, we’ll focus on how who each person knows changes the shape of the communities we are a part of. We’ll also learn how those different shapes drive outcomes for us and the people we care about.