This is the 10th post in a series. If you’re not familiar with how to read network graphs, you might prefer to start with Concept 1 or Concept 2.

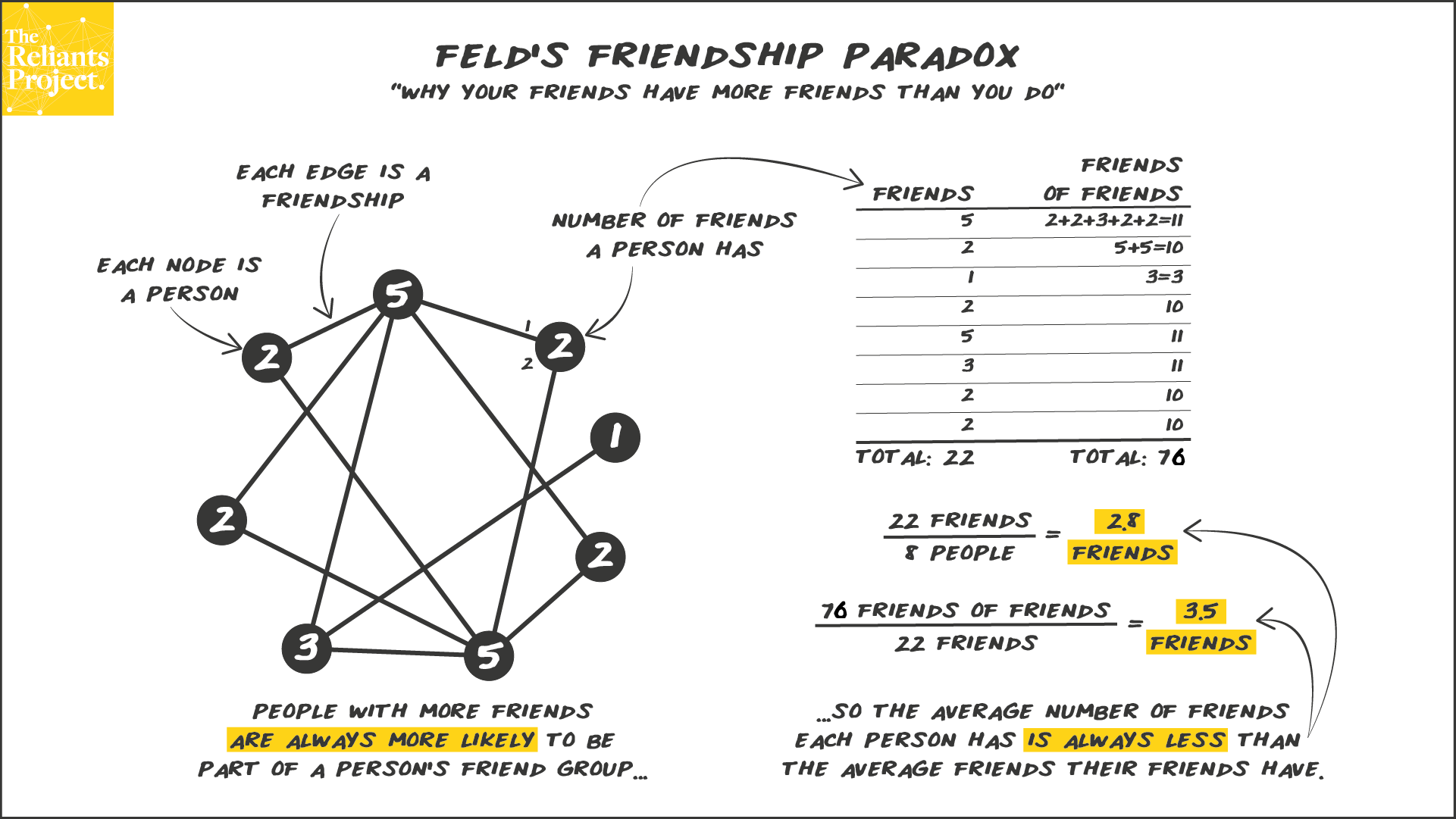

The friendship paradox was first identified by Scott Feld in 1991, which he wrote about in his paper “Why your friends have more friends than you do”. He proved mathematically that the average number of friends a person has is always less than the average number of friends that person’s friends has. Since there are some people with many friendships and others with few, those with many friendships show up more often in friend groups.

In this example, there are two people who have 5 friends on the left-hand-side. As a result, almost everyone is connected to one or the other. Only one person isn’t connected to either of them, and they have 1 friend. This skews the average number of friends of friends to be much higher because each person with 5 friends shows up in almost every friend circle. On the right-hand-side, we can see that the person with 1 friend has 3 friends of friends, where the rest of the group has either 10 or 11. If you have 1, 2, or 3 friends (most of the people in this example), you will feel like your friends have more friends than you do.

Since it is common for people to compare themselves to others, Feld explained that they were likely to feel inadequate and that this wouldn’t be a helpful comparison to make. This concept can be generalised to many other characteristics, such as twitter followers, co-author networks and income. People often refer to it in the context of social media, where people perceive that their friends are more popular, go on vacation more or have more exciting lives than they do.

The challenge is that most people have a hard time internalising this, since it seems so counter-intuitive. As a result, we try to “keep up with the Jones”, “get FOMO” or feel anxiety around not being able to measure up.

Ready for the next concept? The next one in the series is Concept 11: Lerman’s Majority Illusion and How it Distorts Our Perception